Southern residents protesting against the Supreme Court decision on school integration.

What is the Southern Manifesto?

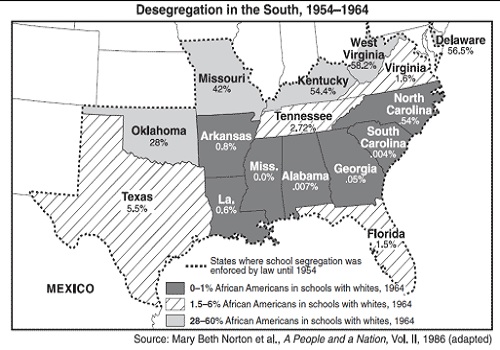

In 1956 politicians from southern states issued the Declaration of Constitutional Principles also known as Southern Manifesto. It denounced the Supreme Court’s decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education as a breach of states’ rights and accused it of abuse of judicial power. The Manifesto was signed by 19 senators and 77 members of the House of Representatives from Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia.

Why was the Southern Manifesto issued?

The ruling in 1954 of the Supreme Court in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka and the reversal of Plessy v. Ferguson angered many southern states who wanted to maintain segregation as part of their status quo. The Supreme Court ruled that public schools must integrate and accept African American students. Southern politicians knew it was just the beginning of desegregation of public facilities; soon it would be transportation, parks, inns, restaurants and shops.

The Manifesto laid the strategy to delay the end of Jim Crow, as segregation laws were known. It would take many years and a many court battles to eliminate the legal barriers that southern states raised to impede integration. In the 1958 Cooper v. Aaron case the Supreme Court held that all states are bound by the Court’s decision and that its interpretation of the Constitution is the “supreme law of the land”

Transcript of the Declaration of Constitutional Principles or Southern Manifesto

The unwarranted decision of the Supreme Court in the public school cases is now bearing the fruit always produced when men substitute naked power for established law.

The Founding Fathers gave us a Constitution of checks and balances because they realized the inescapable lesson of history that no man or group of men can be safely entrusted with unlimited power. They framed this Constitution with its provisions for change by amendment in order to secure the fundamentals of government against the dangers of temporary popular passion or the personal predilections of public officeholders.

We regard the decision of the Supreme Court in the school cases as clear abuse of judicial power. It climaxes a trend in the Federal judiciary undertaking to legislate, in derogation of the authority of Congress, and to encroach upon the reserved rights of the states and the people.

The original Constitutional does not mention education. Neither does the Fourteenth Amendment nor any other amendment. The debates preceding the submission of the Fourteenth Amendment clearly show that th ere was no intent that it should affect the systems of education maintained by the states.

The very Congress which proposed the amendment subsequently provided for segregated schools in the District of Columbia.

When the amendment was adopted in 1868, there were thirty-seven states of the Union. Every one of the twenty-six states that had any substantial racial differences among its people either approved the operation of segregated schools already in existence or subsequently established such schools by action of the same law-making body which considered the Fourteenth Amendment.

As admitted by the Supreme Court in the public school case (Brown v. Board of Education), the doctrine of separate but equal schools “apparently originated in Roberts v. City of Boston (1849), upholding school segregation against attack as being violative of a state constitutional guarantee of equality.” This constitutional doctrine began in the North-not in the South-and it was followed not only in Massachusetts but in Connecticut, New York, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, Ohio, Pennsylvania and other northern states until they, exercising their rights as states through the constitutional processes of local self-government, changed their school systems.

In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 the Supreme Court expressly declared that under the Fourteenth Amendment no person was denied any of his rights if the states provided separate but equal public facilities. This decision has been followed in many other cases. It is notable that the Supreme Court, speaking through Chief Justice Taft, a former President of the United States, unanimously declared in 1927 in Lum v. Rice that the “separate but equal” principle is “* * * within the discretion of the state in regulating its public schools and does not conflict with the Fourteenth Amendment.”

This interpretation, restated time and again, became a part of the life of the people of many of the states and confirmed their habits, customs, traditions and way of life. It is founded on elemental humanity and common sense, for parents should not be deprived by Government of the right to direct the lives and education of their own children.

Though there has been no constitutional amendment or act of Congress changing this established legal principle almost a century old, the Supreme Court of the United States, with no legal basis for such action, undertook to exercise their naked judicial power and substituted their personal political and social ideas for the established law of the land.

This unwarranted exercise of power by the court, contrary to the Constitution, is creating chaos and confusion in the states principally affected. It is destroying the amicable relations between the white and Negro races that have been created through ninety years of patient effort by the good people of both races. It has planted hatred and suspicion where there has been heretofore friendship and understanding.

Without regard to the consent of the governed, outside agitators are threatening immediate and revolutionary changes in our public school systems. If done, this is certain to destroy the system of public education in some of the states.

With the gravest concern for the explosive and dangerous condition created by this decision and inflamed by outside meddlers.

We reaffirm our reliance on the Constitution as the fundamental law of the land.

We decry the Supreme Court’s encroachments on rights reserved to the states and to the people, contrary to established law and to the Constitution.

We commend the motives of those states which have declared the intention to resist forced integration by any lawful means.

We appeal to the states and people who are not directly affected by these decisions to consider the constitutional principles involved against the time when they too, on issues vital to them, may be the victims of judicial encroachment.

Even though we constitute a minority in the present congress, we have full faith that a majority of the American people believe in the dual system of government which has enabled us to achieve our greatness and will in time demand that the reserved rights of the states and of the people be made secure against judicial usurpation.

We pledge ourselves to use all lawful means to bring about a reversal of this decision which is contrary to the Constitution and to prevent the use of force in its implementation.

In this trying period, as we all seek to right this wrong, we appeal to our people not to be provoked by the agitators and troublemakers invading our states and to scrupulously refrain from disorder and lawless acts.

Signed by:

Members of the United States Senate:

Alabama-John Sparkman and Lister Hill.

Arkansas-J. W. Fulbright and John L. McClellan.

Florida-George A. Smathers and Spessard L. Holland.

Georgia-Walter F. George and Richard B. Russell.

Louisiana-Allen J. Ellender and Russell B. Lono.

Mississippi-John Stennis and James O. Eastland.

North Carolina-Sam J. Ervin Jr. and W. Kerr Scott.

South Carolina-Strom Thurmon and Olin D. Johnston.

Texas-Price Daniel.

Virginia-Harry F. Bird and A. Willis Robertson.

Members of the United States House of Representatives:

Alabama-Frank J. Boykin, George M. Grant, George M. Andrews, Kenneth R. Roberts, Albert Rains, Armistead I. Selden Jr., Carl Elliott, Robert E. Jones and George Huddleston Jr.

Arkansas-E. C. Gathings, Wilbur D. Mills, James W. Trimble, Oren Harris, Brooks Hays, F. W. Norrell.

Florida-Charles E. Bennett Robert L. Sikes, A. S. Her Jr., Paul G. Rogers, James A. Haley, D. R. Matthews.

Georgia-Prince H. Preston, John L. Pilcher, E. L. Forrester, John James Flint Jr., James C. Davis, Carl Vinson, Henderson Lanham, Iris F. Blitch, Phil M. Landrum, Paul Brown.

Louisiana-F. Edward Hebert, Hale Boggs, Edwin E. Willis, Overton Brooks, Otto E. Passman, James H. Morrison, T. Ashton Thompson, George S. Long.

Mississippi-Thomas G. Abernethy, Jamie L. Whitten, Frank E. Smith, John Bell Williams, Arthur Winsted, William M. Colmer.

North Carolina-Herbert C. Bonner, L. H. Fountain, Graham A. Barden, Carl T. Durham, F. Ertel Carlyle, Hugh Q. Alexander, Woodrow W. Jones, George A. Shuford.

South Carolina-L. Mendel Rivers, John J. Riley, W. J. Bryan Dorn, Robert T. Ashmore, James P. Richards, John L. McMillan.

Tennessee-James B. Frazier Jr., Tom Murray, Jere Cooper, Clifford Davis.

Texas-Wright Patman, John Dowdy, Walter Rogers, O. C. Fisher.

Virginia-Edward J. Robeson Jr., Porter Hardy Jr., J. Vaughan Gary, Watkins M. Abbitt, William M. Tuck, Richard H. Poff, Burr P. Harrison, Howard W. Smith, W. Pat Jennings, Joel T. Brothill.

Source: Congressional Record, 84th Congress Second Session. Vol. 102, part 4. Washington, D.C.: Governmental Printing Office, 1956.